CFI Newsletter #20: Cooling a Warming India

+ fake snow and the Winter Olympics, implications of decarbonizing steel, water stress in consumer durables, oil & gas funding by a net-zero alliance

The Climake Newsletter offers quick digests and insights around what is happening in climate finance. While Climake’s current focus of work is India-centric, we will capture a global perspective of climate finance in this newsletter on a fortnightly basis.

Every 4 years Shravan’s family gets into an argument over whether the sports of the Winter Olympics are better than those of the Summer Olympics (with curling as one of the sports on offer, the obvious answer has to be the Winter Olympics).

Beijing, a city that barely sees any natural snow, claimed that the 2022 edition it hosted was the greenest Winter Olympics on offer, but its use of fake snow in all the outdoor winter events - requiring 730,000m³ of surface water for snowmaking (equivalent to almost 300 Olympic-sized swimming pools) - leaves us wondering how this claim stands up.

The use of water for artificial snow is a problem for its obvious environmental issue, especially so as water is an increasingly constrained sources, and for more practical issues on it being not as up-to-mark as real snow.

There is a real concern that as global temperatures increase, even places that on paper would be thought to be more suited for hosting the Winter Olympics will struggle to host them, even if the mighty sport of curling - played on an indoor artificial ice rink - should, in theory, be unscathed.

Water and snow are definitely on our minds as we talk about the true cost of industrial water withdrawals. Also in this newsletter, our take on what it will take to keep India cool as the weather continues to heat up.

Climate Finance by the Numbers

30%

The expected increase in production costs, by 2050, of a decarbonised steel sector

Steel production accounts for 8% of global CO₂ emissions. It’s decarbonization story shows the complexity of moving from net-zero commitments to achieving actual results across sectors and geographies.

The promising part is that the technology to make 80% of the steel sector’s GHG emissions net-zero is available. These emissions comes from energy use, mainly from the use of coal to achieve the high temperatures in most common blast furnace - basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) plants.

Electric arc furnaces (ERF) - which constitute around 25% of the world’s steel output - operate entirely on electricity and can replace BF-BOF plants. If the grid is powered by 100% renewables, the energy used to make steel would contribute 0 GHG emissions. While the largest world’s steel players are located in countries with fossil-fuel driven grids, they all have net-zero commitments for renewables to be dominant in their grid energy mix.

Investments to decarbonize steel are estimated at USD 4.4 trillion over the next 30 years. A large part will go towards the adoption of ERFs, but a significant amount will also go towards deploying technologies that still need to be developed and made commercially ready.

Green hydrogen is an alternative to reduce the use of natural gas, used as a reducing agent to convert iron ore to steel, which makes up about 20% of the sector’s emissions. While it has sky-rocketed in policy and technology development pushes, green hydrogen will take time to get commercially widespread.

McKinsey projects that despite advances, 35% of the world’s steel by 2050 will be made from coal-derived blast furnaces. These will require carbon-capture-and-storage (CCS) for net-zero. CCS is nascent, still in a technology discovery and piloting stage, and a long way from being commercially widespread.

This is not the sector’s only challenge. All this decarbonization is expected to lead to a 30% increase in production costs of steel by 2050. The products and goods in downstream sectors reliant on steel - from buildings, to automobiles - will, in theory, become more expensive.

But this may actually not be too much of a negative overall.

Buildings constitute about 50% of steel’s use globally. Increased costs may lead to less building stock, less unused buildings, less resource use, and less GHG emissions - China’s empty properties today are said to be sufficient to house around 90m people. It can even open up the opportunity for alternative materials to be adopted, such as cross-laminated timber replacing steel rebar in building and construction.

19-27%

The consumer staples industry accounts for more than two-thirds of global water withdrawals. And a recent report from Barclays, using CDP data shows these food, drinks and household/personal care businesses have quite a role to play in causing water stress and potentially reversing it.

Water withdrawals have more than doubled since 1960. This water stress, unfortunately, get a lot less mindshare today than carbon. While some giants like Diageo disclose and quantify the impact of water stress on their business, most others do not. Even for those who do, CDP estimates that the true cost of water withdrawals might be 3-5X more than what is currently disclosed.

The good news though is positive water action may be a lot cheaper than a route to net zero. In 2020, food and beverage companies reported to CDP that they estimated the financial impact of water risk at USD196 billion, while fixing it will take just USD11 billion.

We wonder why we are not seeing more water action if the cost of inaction is so much higher. The answer, we believe, lies in the fact water has traditionally been a near-free resource. Even when corporations require the need for action on water stress, it often gets lower priority than say, renewable energy that has both an economic and climate benefit.

This could change as water scarcity starts to impact businesses or if governments start putting a value on water withdrawals. In India, the state of Maharashtra is charging water intensive industries a 4X premium for buying bulk water. But without a further push to recycle and reuse water, there simply hasn’t been enough economic incentive for water innovation to thrive.

We are now starting to see pockets of change with a handful of startups emerging in grey water and industrial wastewater management, largely prompted by government policies. Much more push is needed to bring the focus back on this increasingly scarce resource.

USD 38 billion

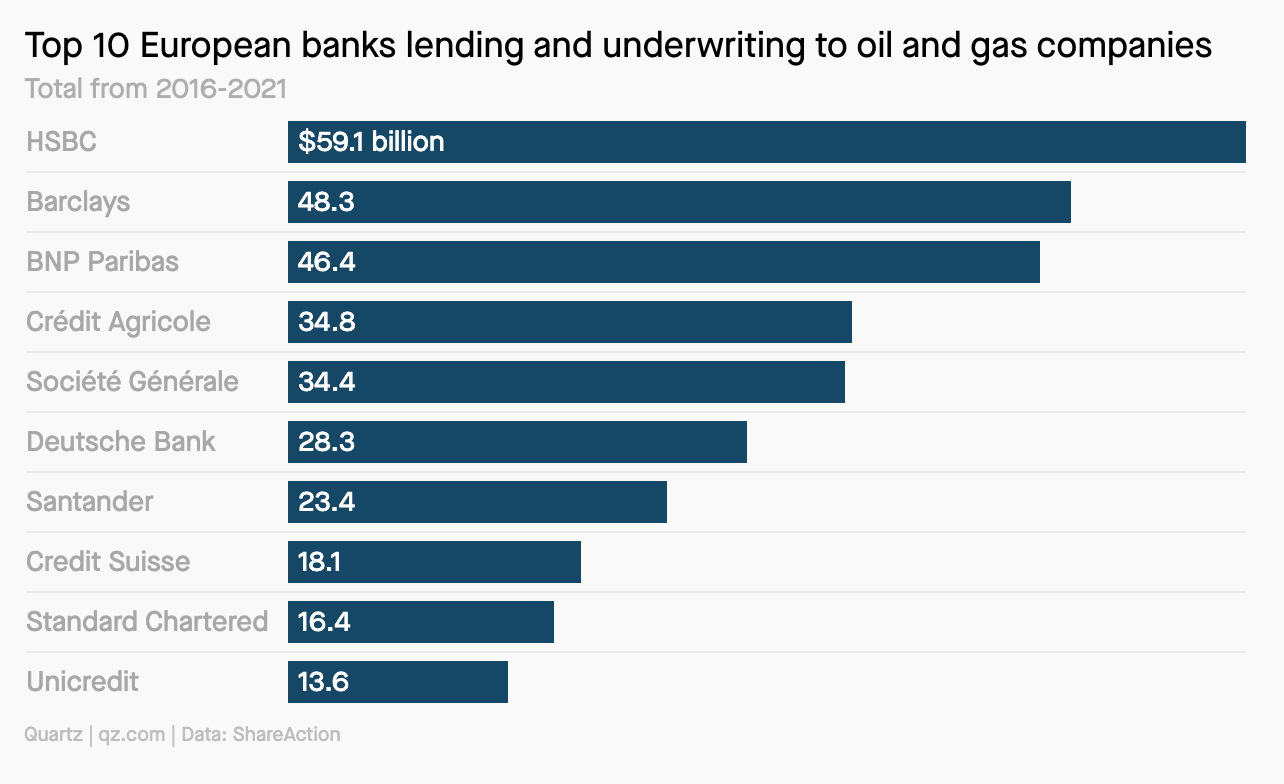

Financing provided by members of Net Zero Banking Alliance to oil and gas industry since April 2021

The International Energy Agency (IEA) believes that there is no room for new oil and gas capacities in any pathway that takes us to net zero emissions by 2050. The oil industry however, continues to plan new capacities and expand production with new projects of around USD 150 billion forecasted for 2022.

Our one hope to curb the growth of conventional energy projects, including shale and Arctic oil projects with high environmental costs, was the move that the banking industry made last year. Net Zero Banking Alliance was formed in April 2021 with an ambition to bring emissions in the portfolios of the largest global lenders to net zero by 2050. Our assumption was that this would naturally lead to the banks stopping funding for any new oil and gas projects.

It appears that we may have been over optimistic in our assumptions. A recent report by ShareAction shows that while specific project funding may have indeed declined, banks continue to support fossil fuel companies via loans for ‘general corporate purposes’ and capital markets underwriting.

Institutional asset managers who are part of the Net Zero Asset Managers Alliance may also have a role to play. It appears that as oil and gas companies sell of their assets in a bid to appease shareholders - an estimated USD 44 billion have been sold since 2018 - these are being lapped up by private equity funds looking for the high yields these assets provide. Just like the wordplay with loans, PE managers are making these energy portfolios part of their ‘growth’ or ‘opportunistic’ funds.

Given the opportunity to build complex structures that capital markets provide, merely stopping project financing for fossil fuels is meaningless. For net zero alliance to be truly impactful, its signatories need to stop funding to fossil fuel businesses in all its forms, rather than provide lip service and opening other channels of support.

THE BIG READ

Cooling a Warming India

As the world faces rising temperatures, the adoption of cooling solutions is likely to increase. But cooling in itself is a contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. How can India expand its cooling infrastructure without adding to its emissions.

Over the past 25 years, India has consistently experienced hotter than average weather temperatures. While average temperatures in certain parts of the country range from 32°C to over 45°C, it has experienced 50°C days in a couple of instances - a temperature level considered unsuitable for humans. Temperatures are likely to rise and 50°C days are likely to be more frequent in the coming years. For a sense for what life is like at this temperature, we just need to look at Jacobabad in Pakistan.

The effects of excess temperatures are significant. Extreme heat is expected to cost the Indian economy USD 450 million through lost productivity by 2030. More worrisome is the rise in global heat wave deaths; from 12,000 deaths annually today to about 250,000 by 2050 if things continue on their current path.

Cooling and air-conditioning is increasingly becoming a need, but its climate story is not just about making life in a warming world more bearable.

How cooling drives climate change

We need to get a bit stats heavy to really see the role of cooling in climate change.

Air conditioning accounts for about 40–60% of peak power demand in summers in Mumbai and New Delhi. By 2030, cooling is likely to account for 20% our total electricity use from the 7% it consumes today. The demand for comfort cooling is expected to drive the total stock of room ACs to over 1 billion by 2050 – a 40-fold growth from 2016. If we take current cooling usage and consumption patterns, approximately 600GW of new power generation capacity would be needed by 2050. On 31st December 2021, India’s total electricity grid capacity stood at 393 GW.

Cooling is a significant demand-side driver of greenhouse gas emissions. And that is without accounting for hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) emissions from the use of refrigerants that help in the refrigeration cycle. HFCs have a global warming potential that is between 670 and 1500 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The UNFCCC estimates that 20% of all GHG emissions from cooling comes from emissions of refrigerants, with the remaining 80% from energy use.

Cooling, if our current use trajectory continues, will offer one of our most ironic feedback loops:

as we experience warmer temperatures, we use more air-conditioners; as we use more air-conditioners, we will experience warmer temperatures.

India is arguably going to be the largest adopter of cooling solutions - refrigeration, air conditioning, cold chains - in the world in the coming decades, and have the largest need for them to be low-carbon and energy efficient.

The India Cooling Action Plan

The good news is the India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP). A focused piece of policy with a 20-year horizon to catalyse a low-carbon and energy efficient change in refrigeration, space air-conditioning, cold chains, and transport air-conditioning, that with 3 targets to reduce the climate change impact of cooling:

reduce cooling demand across sectors by 20% to 25% by 2037-38

reduce refrigerant demand by 25% to 30% by 2037-38

reduce cooling energy requirements by 25% to 40% by 2037-38

It is significant not just for its objectives. The ICAP would make cooling the second demand-side sector to have a climate-friendly policy after electric mobility (although the ICAP is more encompassing in its intended sector transition and length than the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicle (FAME)). This moves beyond the trend which has largely focused only on the supply-side of renewable and clean energy targets.

Recognising that new cooling solutions are needed, the ICAP has instituted its own innovation discovery program, the Global Cooling Prize, the first a call for 5X air-conditioners - a cooling solution that has one-fifth of the climate impact of the commonly sold room AC units in the market today.

The ICAP goes some way to provide direction. For instance, the Rocky Mountain Institute estimated that if the 5X air-conditioners become adopted wholesale, India can remove 400 GW of new power generation by 2050, a saving of around USD 380 billion, and mitigate up to 16 gigatons of CO2 emission by 2050. For context, India’s total GHG emissions in 2019 was 3.15 gigatons.

The not so good news is that the ICAP has not actually gone very far in its 2 years. The promise of the India Cooling Action Plan is thin on details around roadmaps for developing and mainstreaming low-carbon, energy-efficient cooling solutions, and, of course, the financing to make this happen.

Cooling Finance

The State of Climate Finance in India 2022, put the expected investment in demand efficiency, which includes heating and cooling at USD 60 billion by 2030.

Financing is central to the issue cooling faces, not just in developing solutions but in also making them accessible to consumers. Take the energy efficiency star rating schemes as an example. In a 2020 study on the sentiment of consumers on energy rating schemes in Tier 2 cities, over 75% of households were aware of the star rating scheme, 70% of people wanted to buy a higher-rated appliances, but only 14% ended up purchasing 4 to 5-star equipments due to the increased cost of higher-rated appliances. At a 20% energy saving, using a 3-star over a 5-star air-conditioner has significant energy use, cost, and GHG impact.

India’s cooling climate finance landscape will need to include:

Innovation funding to develop new promising solutions. (The Global Cooling Prize is one initiative that supports this but it is just one, and it is limited, providing a one-time prize when innovation funding needs support for prototype development, piloting, testing. It is also unclear how regular the Global Cooling Prize is intended to be.);

Growth capital, in the form of both debt and equity capital for scaling and growing offerings;

Concessional financing to making the adoption of these technologies affordable to customers and consumers; or upfront financing that lets customers pay for 5-star equipments as they realise energy savings over time.

Delivering on these 3 broad forms of capital will rely on a myriad of instruments and structures, from debt, to equity, to multiple in between the two; and rely on a range of financing providers that will cut across, government, development finance, private equity, and other institutional plays.

The promising news is that institutions from the World Bank to UNEP, through the Cool Coalition, are bullish in bringing development finance capital to support ICAP, making the sort of right noise and moves to bring more life to the ICAP. Development finance is likely to lead the charge for more capital to enter the space, but it urgently needs to be met by early-stage and innovation capital that will support product development, piloting and early-adoption, without which DFIs large-scale funding cannot be deployed to get solutions to growth and scale. The gap in cooling makes innovation and early-stage finance especially important, more on that later.

Cooling’s opportunity will be driven by equity (not the finance kind)

Cooling will face the oft-repeated problem of most sustainability-focused products - that they are (often a more expensive upfront) alternative to an existing product. Air-conditioners, for example, have a 10 to 15 year lifetime, more than half the time period of the ICAP to reduce energy consumption by 25% to 40%.

The traditional attitude of most customers is to wait to replace it after the equipment is broken or drops a level of performance to necessitate replacing. This behaviour does not help. It reduces the pace of urgency to mainstream climate-positive cooling solutions, and invest in production and distribution channels to meet the shift toward. It is quite likely that early adoption of climate-positive air-conditioning systems, especially, will require trade-in incentives for buyers to replace their perfectly functioning but energy inefficient or HFC refrigerant operated cooling systems. A model that Ather Electric followed in rolling out its 2-wheeler scooters.

But the market opportunity of climate-positive cooling is not just about replacing energy inefficient or HFC refrigerants-using technologies.

Cooling is going to become an equity issue of making it more accessible and available, not one of convenience and comfort. Only 10% of households in India have air-conditioning, rising temperatures mean we have to ensure that significantly more people are able to access it. Most of the building stock in Indian cities that will be around by 2030 (and their air-conditioning) is yet to be built. Cold chain infrastructure has a gap of between 10% to 90% of different facilities that is contributing to the over USD 15 billion of food waste annually. This demand will increase as food security requirements grow, and stresses from extreme weathers will require produce to be better stored.

This is unlike India’s other big demand-driven climate sector: electric vehicles. The adoption of electric mobility solutions is almost exclusively about replacing existing fossil-fuel driven internal combustion engine vehicles.

The contrast paths of climate-friendly air-conditioning and cold storage

The contrasting paths in air-conditioning and cold storage to get towards a climate-friendly outlook, emphasizes the complexity in cooling. For instance, financing to make cold chains climate-friendly is going to be significantly more tricky than air-conditioning.

The difference between the product sectors comes down to the maturity of the markets (cold chains and coolers are a lot more nascent) and type of companies that will drive the climate-friendly path for these sectors.

Air-conditioning will be driven by established global and national players - e.g. Godrej, Voltas, Carrier - whom we expect to drive the adoption of climate-positive solutions. Technology development - to the 5X level mention above - is nascent enough for technology development to come from either these OEMs or from new startups. The Global Cooling Prize did reflect in this in the mix of global giants and small startup outfits in the final shortlist of solutions that were selected before the winners (both incumbents) were selected.

But incumbents will be a mainstay through their established manufacturing, supply, and distribution channels of these asset-heavy products. Large-scale commercial and industrial spaces are likely to be the initial customer audience for air-conditioning at scale. Unlike with EVs, the transition to develop more energy-efficient air-conditioning is likely to be easier for OEMs to switch, compared to automakers moving to electric vehicles from the internal combustion engine.

In cold chains, however, (which will range from cooling around agriculture, food, beverages, and also increasingly vaccines in these COVID-19 times) emergent and maturing startups will play a more prominent role in growing the sector. Factors from the need to be self-sufficient in grid-disconnected rural areas, to the sheer gap in cold storage options today, will offer more opportunities for new entrants to the space.

Innovation and early-stage funding is likely to play a more prominent role here, but growth capital will be equally critical in the ICAP’s 20-year horizon as India’s food security needs shape up.

But financing institutions are not at par with the financing needs of cold chains, especially around end-user financing and asset financing, which is pretty crucial for market adoption. In our day jobs, we see this on a regular basis. Highly promising cold storage companies looking to access unlock end-user financing to make their products affordable until economies of scale reduce prices further; and financing institutions just unsuited to meeting this need, with a combination of high interest rates, onerous processes, lack of guarantees, and skepticism about nascent sectors, all contributing to limit growth.

These are not problems that the air-conditioning industry is likely to face as they are driven by large incumbents, not only in the production of air-conditioners, but even in the customer base of climate-friendly cooling systems: large real estate and property owners. (Contrast this to cold chains which, other than a few large agriculture majors, will have a customer market dominated around small-hold institutions and small establishments). As financing can be linked to these established organizations, institutions are likely to be more willing to engage on more supportive terms, as compared to cold chains.

Cooling a warming world

Energy-efficient, climate friendly cooling should, in theory, have less barriers and greater demand to become the norm in the future. But we are almost starting from a blank slate today. 5-star cooling air-conditioners make up around 12% of the market in 2019, dropping from 22% in 2017. Solar-powered cold storage solutions are nascent, with their market size in India estimated at around USD 90 million in 2018 against a market potential of at least USD 20 billion.

Cooling will need more of a look-in in a warming world.

That’s it for Edition #20 of our newsletter.

As always, send all feedback, compliments and brickbats our way. And of course, we do appreciate you spreading the word about this newsletter.

We’re growing to build something collaborative with you and the more the merrier!

Best,

Simmi Sareen and Shravan Shankar

Thanks Simmi and Shravan! Your newsletter is very helpful in appreciating the challenges and opportunities about the impact of Climate Change. Best Wishes, Paresh