CFI Newsletter #6: India's Small Businesses and Climate Action

+ zero energy investments in India, corporate renewable energy trends, what India's first solar InvIT offers

The Climate Finance Initiative Newsletter offers quick digests and insights around what is happening in climate finance. While the Climate Finance Initiative’s current focus of work is India-centric, we will capture a global perspective of climate finance in this newsletter on a fortnightly basis.

The Climate Finance Initiative’s wider aim is to build a more collaborative ecosystem around climate finance. Towards this end, we want the CFI newsletter to host and be a space to feature insights from organizations and individuals who are influencing and working on climate action and financing in different ways.

Today we are thrilled to have our first guest collaborator post from Richenda van Leeuwen, the Executive Director of the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) focused on small businesses and Indian climate action.

SMEs account for almost 90% of enterprises globally. From clean energy resilience in agricultural small-holdings to greening manufacturing supply chains across various sectors, the need for tackling climate action in and for SMEs is urgent and faces a lot of complexity to make progress. We are big fans of the work ANDE does in supporting small and growing businesses (SGBs) and the support organizations that work with them, and we do feel they are a great voice to offer insights on their approach to climate action.

If you would like to hear from a particular voice, or if you would like to reach out to us yourself for a collaborator post, let us know!

Climate Finance by the Numbers

0 (Zero)

The number of energy investment deals in 2020 in India as per the Impact Investors Council

We should begin by saying that we, at CFI HQ, really do like the work the Impact Investor Council (IIC) does to strengthen impact investing in India. But their definition of what comes under impact investing requires scrutiny.

Let us clear that number first. The number of energy investments in India in 2020 was not a zero as the IIC report claims. Leaving aside renewable energy investments, which would significantly skew numbers, startups in areas related to energy - battery storage, electric mobility, and energy efficiency to name a few - have raised a not-insignificant amount of investment in 2020.

The IIC does not disregard energy investments. The issue, however, is how it accounts for it in a narrow definition, which hinges around the word, “affordable”:

“Enterprises which offer access to affordable clean energy services or products, helping the environment and the consumer.”

This definition is derived from the organization’s wider stated purpose of encouraging private capital to bridge the social investment gap.

The IIC’s definition of impact investing revolves around social-focus first intervention areas, particularly interventions that benefit specific areas of the Indian population: low-income / under-served / rural areas. While these are important areas, it excludes environmental and climate action-first interventions, often implemented towards other areas, from how they view impact investing.

This is more important than just a quibble about terminology.

To soon-to-be entrepreneurs, prospective backers, investors, policymakers, and almost all stakeholders, impact investing is synonymous with investments that create social and environmental impact. The IIC, being the leading national industry body for impact investing, influences how its stakeholders understand what investing in sustainability is. Disregarding environmental-first interventions has consequences as it reduces support structures and financing for climate mitigation and adaptation, energy efficiency, pollution mitigation, and other such areas.

The IIC is certainly not at fault for the ineffective state of investment and funding in environmental and climate action in India, but it is an influential enough institution to start shifts that improve it, especially as it is looking to define what impact investment in India should be, which is something we would urge them to look at.

And climate investments do and should fit into their definition: all environmental-first interventions end up having a social impact. Climate change affects vulnerable populations the most. Cleantech innovations in renewable energy systems, energy-efficient products and electric mobility all have the potential to mitigate the negative impact of climate change and should qualify as investments creating positive environmental and social impact.

50%, 380MW

Amazon’s purchase commitment amounts to 50% of the energy expected to be generated in Shell’s upcoming windfarm in Europe’s North Sea region. It is also its largest renewable energy commitment. 50% and 380MW are not particularly mind-blowing numbers, especially considering the mammoth 8200 MW Sinan Korea Offshore wind farm planned in South Korea and a whole host of other upcoming wind farms with capacities in the GW range.

But we found it indicative of a potentially fascinating and important shift in how renewables get more mainstreamed by moving from a government or investor-driven model of financing to a market or customer-driven model of financing.

Companies like Amazon investing in renewable energy capacities can make such setups more viable for renewable energy operators. More importantly, it is reflective of greater trust and less risk aversion from companies to invest in renewables. Captive renewable energy farms are not new, but the scale and numbers that companies are looking to invest in shows a push through mainstreaming.

Big Tech players are seemingly leading the charge. Apple’s stance, in particular, of having all its suppliers procure 100% of their energy from renewable energy sources will have a multiplier effect. It has led to the largest corporate renewable energy deal, with the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, one of Apple’s largest suppliers, inking a deal with the Danish wind farm operator Orsted to purchase 100% of the energy generated from their 920 MW wind farm of the coast of Taiwan.

1.5 GW

Solar projects to be acquired by India’s First Solar InvIT

Virescent, a newly set up infrastructure investment trust (InvIT), is looking to acquire 1.5 gigawatts of renewable energy assets over the next 2-3 years. Apart from the obvious benefit of bringing an additional INR 6,000 crore (USD 800 million) into climate action, there is much that we find exciting about the first solar InvIT in India.

InvITs are typically set up as long term investment vehicles to provide consistent returns to their investors. A solar InvIT backed by a major global investor (KKR) shows significant confidence in the maturity of the solar sector in India. For an InvIT to work, investors need to believe that not only are the solar assets generating enough cash flows to pay a return on their capital today, but will continue to do so over a 10-12 year horizon.

The InvIT structure is also well suited to attract low cost debt capital from foreign investors, a benefit that the Indian government recognised in the recent budget. The recent change in regulations allows foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) to invest in the non convertible debentures (NCDs) issued by InvITs. This opens up the structure as an investment opportunity for several pension funds and sovereign funds who were not willing to take equity risks earlier and can now invest in debt instruments issued by an InvIT.

If we look back at the experience of real estate trusts (REITs) in India, an investment by a large global fund like KKR is often the leading indicator of many more to follow. The demand for electricity in India is likely to more than double by 2050, with new renewable energy capacities accounting for bulk of the increased production. Crisil projects that InvITs will raise an additional USD 100 billion in capital by 2025. If KKR’s InvIT proves to be the first of many - encouraging other funds like Blackrock and Blackstone to follow suit - a lot of this $100 billion may find its way to meeting the capital gap that exists today to fund new renewable capacity and climate action in India.

THE BIG READ

Small Businesses and Indian Climate Action

SMEs make up a large part of businesses, jobs, and GHG emissions. A concerted effort towards climate action in India has to include how we engage and support small and growing businesses

Small and medium-sized enterprises, according to the World Bank, represent about 90% of businesses globally, and more than half of all employment. According to its estimates, 600 million jobs will be needed globally from now until 2030, making SME development a high priority for governments around the world. This is particularly true for India, given that by 2027 it is expected to become the world’s most populous country.

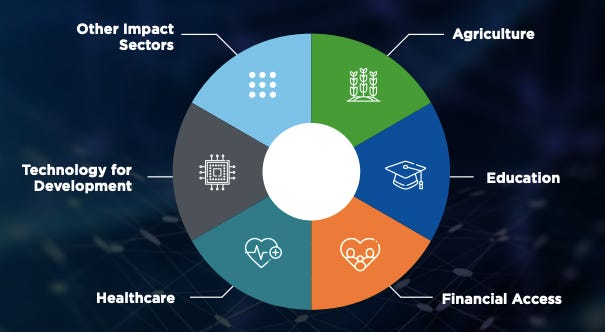

The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) focuses on supporting the enabling ecosystems for small, growing businesses (SGBs) in developing economies to thrive, to maximize their job creation and climate, environmental and social benefit contribution.

In India, where ANDE has been working for the last nine years with a diverse member network of local business support intermediaries, the energy transition presents a vast range of opportunities for SGBs. While the energy sector comprises the bulk of Indian emissions, other sectors with significant emissions include industrial processes, land-use changes, forestry, and waste, all of which intersect with the small business sector in India.

Climate Action’s Paths and Opportunities

As outlined in ANDE’s recent climate brief, adopting a circular economy path in the food and agriculture sector in India presents the possibility of creating annual benefits of: US$ 61 billion, 31% fewer GHG emissions, 71% less synthetic fertilizer and pesticide usage, and a 49% reduction in water consumed by 2050.

Similarly, the Indian textile industry is a major contributor to waste and pollution with nearly 5% of all landfill space being taken up by textile waste and 20% of all freshwater pollution being made by textile treatment and dyeing plants. Globally, the textile industry emits 1.2 billion tons of CO2 equivalent annually, nearly as much as the auto industry, so adopting a circular economy path could have significant benefits for the industry.

Opportunities range from the continued growth of renewable energy, both at a large scale and also through mini-grids for those without grid access, to development of the technologies necessary for the integration of renewables into the grid for scheduling, forecasting, demand-side management, and integration of smart meters. Development of energy storage is critical to enable a move to lower-carbon energy sources, as well as new or scaled waste-to-energy and energy efficiency measures. A transition to green transportation, including electric vehicles (EVs), such as has already taken place with electric rickshaws. These solutions promise not only to lower carbon emissions but also help address one cause of chronic urban pollution.

A 2019 survey by Power for All and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) reported that 95,000 direct formal jobs and around 210,000 informal jobs were created in the distributed renewable energy sector in India in 2017-18. However, women’s participation in the sector remains low. Indian women constitute only about 11% of those working for—let alone leading—rooftop solar companies, compared to 32% globally. There is a clear opportunity to align the current government’s focus on entrepreneurship and innovation, including via the Atal Innovation Mission. What is needed is stronger targeted support for women’s engagement in the green economy as entrepreneurs, helping to address the particular ingrained challenges that they face in building their businesses.

But climate action cannot be construed as only a government responsibility. Private investment into the sector is largely deployed, either in late-stage proven technologies such as wind, solar, and increasingly EVs, or in very early-stage companies via grants and incubation or acceleration support. There remains insufficient funding directed towards businesses that need the capital to de-risk and become scalable and commercially viable. There is also a need to better understand the needs of social enterprises in the sector, and to align investment with what small and growing businesses (SGBs) that can provide immense value to local communities in building resilience truly need.

Early-Stage Risk Capital needs to be more accessible

Early-stage risk capital continues to be inaccessible to innovators and entrepreneurs in the climate arena. Venture capital models, as widely practised, are not the ideal solution for many climate innovations due to their different development cycle, market structure, and risk-reward profile. On a positive note, debt funding is increasingly available in the sector, with a range of financial instruments provided by organizations such as Caspian, Yunus Social Business, Tata Cleantech, Ckers, Samunnati, Shell Foundation, GreenFunder, NABARD, and programs via the State Bank of India and Punjab National Bank. They provide a full range of products from venture debt and working capital to asset finance, invoice discounting, and project finance. However, a challenge noted by debt providers is that equity is generally required to cover a percentage of the proposed use. Certain lenders have identified the dearth of equity funding in the market as a significant business challenge. ANDE’s own global research has also shown that women entrepreneurs in particular struggle to access equity to grow their businesses across many sectors, not only in the climate arena.

ANDE members have identified some potential approaches to addressing capital issues. First, help climate entrepreneurs build more partnerships with larger corporates (as buyers) - through “reverse pitches.” Some corporates have deep research and development budgets, but often do not have strong linkages with the startup/SGB community in emerging and frontier markets. Second, make more patient capital available to support early-stage or high-risk innovations, ideally via a blended finance mechanism that already has the follow-up capital lined up.

Initiatives to drive more money into the sector remain extremely important. The recent launch of Climate Angels by GoMassive Earth Network, an early-stage investment syndication platform for pollution reduction and climate tech, is one such approach.

Despite the challenges still facing the sector, there are some good examples of promising approaches. For instance, the Circular Apparel Innovation Factory in India’s stated mission is to “build the ecosystem and capabilities to accelerate the transition of the apparel & textile industry towards circularity”. More such ecosystem approaches are needed, alongside targeted earlier stage and patient capital that helps to address the needs of SGBs to help them scale. This can also support women entrepreneurship and create the green jobs that can help propel India into a thriving low carbon economy of the future.

The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and business support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs can create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits.

Engaging with CFI

As always, if you are keen to engage or talk to us on our work plans (check out the deck here) or if you have something of your own to collaborate on, reach out to us below!

That’s it for Edition #6 of our newsletter, our first collaborator edition.

As always, send all feedback, compliments and brickbats our way. And of course, we do appreciate you spreading the word about this newsletter.

We’re growing to build something collaborative with you and the more the merrier!

Best,

Simmi Sareen and Shravan Shankar